By Beverly Bryan

Barrett Martin, best known as the drummer for Seattle grunge rockers Screaming Trees, was an integral part of Seattle's music scene in the 1980s and '90s. The drummer, producer, and composer has played on more than one hundred albums, from records by R.E.M. to Queens of the Stone Age, and has circled the globe on tour. And today, Friday, January 19th, his project Walking Papers -- featuring Jefferson Angell (The Missionary Position), Benjamin Anderson (The Missionary Position), and Duff McKagan (Guns N' Roses, Velvet Revolver, fellow Raw Power band member) -- release their second full-length, WP2, via Loud & Proud Records.

He also holds a Master's Degree in Ethnology and Linguistics, and is now a professor of music at Antioch University. His adventures as a musician, researcher, and world traveler have taken him around the world: from Senegal, where he traveled to study with griot drum master Mapathe Diop; to Cuba, where he sat in with Cuban musicians as a cultural diplomat. He's worked in the studio with delta blues guitarist CeDell Davis and spent time in the Peruvian Amazon with Shipibo shaman and singer Herlinda Agustin Fernandez.

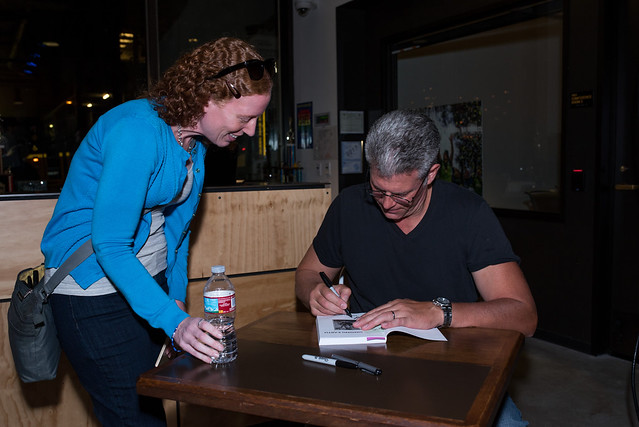

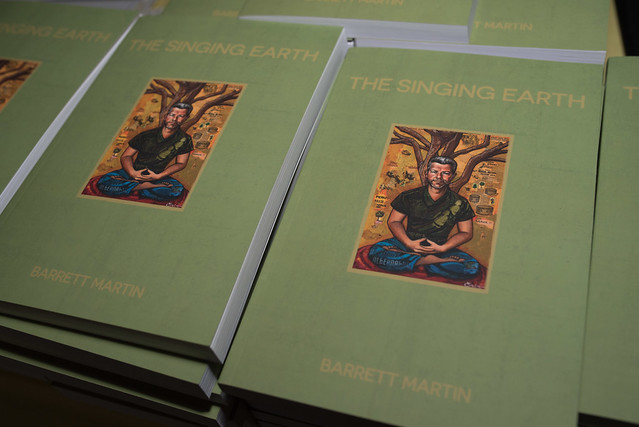

His musical travelogue, The Singing Earth, weaves his encounters with musicians from varied musical traditions into an investigation of the links between music, community, and the natural world. As part of Songbook: KEXP’s Music & Literature Series, the book provided a jumping off point for a thought-provoking dialogue about the role music plays in human life. In this live interview with DJ Kevin Cole, host of The Afternoon Show on KEXP, Martin looked back on a lifetime of music and travel. Watch video, and read edited excerpts from his chat with Martin below.

The book is beautiful and the writing just blew me away. It's like a trans-continental travelogue that chronicles your journeys over three decades across six continents in 14 different musical regions of the world. I think maybe one of the big points of the book is ultimately how that all ties into the earth and our environment.

Well, the reason why I called it The Singing Earth is over the course of 30 years of traveling, and a lot of that was in playing in rock bands, but more than half of it was just me putting on a backpack and taking a field recorder and going out into the jungle or the desert or wherever I happened to be going on that particular trip. And over the course of time, I started to really feel it in my body and in my in my soul how deeply connected music is to the landscape and the people that live in that landscape and the way they are expressing it through their culture. And so I wanted to write a book. I mean somebody asked me about this a little bit earlier. This book started with about a thousand pages of research, a lot of it that I did in graduate school and when I was a music professor I just continued to do research. But I realized that I wanted to write a book for anybody. You don't have to be a musician, you don't have to know music theory and you could learn about music around the world in about 200 pages. So I tried to write it.

Let's go to the beginning and go to Seattle. You studied music in college and were really more of a jazz drummer, or at least you had those chops. You moved from Bellingham to Seattle in the late '80s, and if you're talking about scenes and environments, Seattle has really changed a lot. It's not even recognizable in some ways as the city of once was. Describe what Seattle was like in 1987 to a 19, 20-year-old.

I was exactly 20 in 1987. The city was dug up. All of downtown had giant trenches because they were putting in the bus tunnels. And so it was really hard to even walk around Seattle and the city had this very tough vibe to it. But I liked it a lot. I had a thousand-square-foot warehouse space on Jackson Street in Chinatown. Cost $250 a month and the first three bands I was in -- Thin Man, Skin Yard, and Screaming Trees -- wrote their albums in that warehouse space. The thing that was really amazing about Seattle is that the music that came out of that -- that really grunge music and everything after that -- that's what Seattle looked like. That's what it felt like was happening. It had a real toughness to it. And I preferred it actually. There's something about a city and a place that's really right in the middle of the action. There's something very cool about it.

How did you get in your first bands? And when you went out, what were the bands at that time and what were the clubs like when you went out?

It was basically a punk band, and we kind of had trouble finding gigs in Seattle because everything was very grungy or starting to become grungy, and we just were not cool. We weren't cool. We had really good songs but it wasn't the right time for us. I had this leather jacket that I'd gotten in Italy and it had all these zippers on it and I thought it was cool, and I went to go see a grunge show at the Vogue which was sort of ground zero and that's where Sub Pop was doing their weekly showcases. And I was standing watching some band and Mark Arm was standing next to me and I knew who Mark was, he didn't know who I was, and he just looked over at me and my shoulder pads and I went in the bathroom and I ripped them out. I did. I ripped them out and threw them in the garbage can.

What about in your travels and how your quest to find out more about music and other cultures around the world?

Well, I would say that in spending time on the road, I played music and did some pretty big shows, most of the major cities of the Western world, all throughout North America, Australia, New Zealand, Europe, and Eastern Europe. One of the things that was happening around the same time was all this world music was starting to come out, and it was coming out on CDs. And this is in the late ’80s and early ’90s and that really started to get me interested in other forms of music. I came from a family that did a lot of traveling, and so I just kind of intuitively started doing that on my own, and I was always looking for music. And so in those journeys, I just discovered some incredible forms of music which really kind of altered me for the rest of my life.

Yesterday you said something interesting. You were talking about playing something from Brazil and you mentioned that in Africa or Brazil or Cuba, the ABC is rhythm. Explain what you meant by that.

Well, Africa is, of course, the source of all rhythm. You know, the oldest rhythms are from Africa. And it's a very organized system in West Africa. A lot of people from all over the world go to West Africa to study these rhythms, and then they go back to their hometowns or if they're in bands, they bring those rhythms back. But what's interesting is that in pretty quick succession in about a three-to-four year period I was invited to study in Senegal with a Wolof drum master who actually also lives here in Seattle and his son is going to play with us tonight. But right after that, I went to Cuba. I was invited to be a musical diplomat with the U.S. State Department to go down and work with musicians in Cuba. So I sort of was thrown in to play with, I mean, drummers that were so much better than I was and I just kind of wanted to sit in the corner and listen, but they were so gracious they pulled me in to play. What an experience.

Can you talk about the role of music and the power of music as an agent of social change?

I've been thinking about this a lot because when I've taught classes at Antioch University, I taught a class about music as social commentary, and a big part of it is about the Civil Rights movement. And the reason why that movement was successful is that it had so much music, all those great songs. You know those soul tunes and those gospel songs that were turned into hits and people would march hand in hand and sing those songs. And I'll tell you what the reason why the neo-Nazis and the white supremacists are ultimately going to fail is that they don't have any good songs.

Where do you think music comes from?

It's a good question. Well, I kind of posit a little bit of an idea in the prelude of the book, you know, music's a language. And so you know in linguistics they talk about the development of words and how the brain started to communicate with other brains using sound. Music is very much the same thing. Some of the theories think that melodic ideas came from imitating bird calls, and certainly the sounds of nature. All of those sounds would have a deep influence on how you conceive. I guess is it humans reflecting on what they hear or heard in nature, probably starting with the rhythm. Melody coming later as the language got more sophisticated or just mirroring the sounds in nature whether they be bird calls or the sound of wind moving through reeds.

For many of us who grew up in the punk era, the sound of the Sex Pistols -- that power, energy, propelled by a sneer -- was life-changing. For me, it was those guitar chords. That sound -- copied over and over by legions of guitarists since -- changed my life on a cold, sunny day in a Victorian hou…

Every Shabazz Palaces record feels like a transmission from a far-off planet. In 2017, the Seattle hip-hop duo took this aesthetic a step further with two records -- Quazarz: Born on a Gangster Star and Quazarz vs. The Jealous Machines. The albums collectively chronicle the story of an alien sent t…