In our yearlong celebration of KEXP's 50 years of excellence, we have found ourselves commemorating 2004 this week. 2004 was particularly significant because it was the year we debuted our weekly punk show, Sonic Reducer. For the occasion, Martin Douglas, features writer, producer, and KEXP Editorial's resident punk, tasked himself with running back his essay collection “Requiem for a Fake Punk” for a sequel.

I don’t remember exactly where I was in Seattle when I heard “Sonic Reducer” for the first time. I was somewhere in Fremont, driving through the neighborhood for the first time after visiting a friend. I might have been turning out of a parking lot; I might have been driving down a hill of some sort. I believe I was just talking to my friend Micah on the phone. What’s more punk than a story with an unreliable narrator, right?

Anyway, I do remember it was a Saturday night and Sonic Reducer, KEXP’s signature punk show, was wrapping up for the evening. This had to have been 2007, as that was the year I bought a beat-up Chevrolet Caprice with a completely rebuilt engine, with cracking Farwest Taxi paint that was in a very past life a cop car. My Caprice had a .350 that could smoke any other car off the line but didn’t have an aftermarket CD player or even a stock cassette deck. Just a digital radio dial, which was probably an astonishing innovation for the year it was manufactured.

So as soon I’d pass Southcenter Mall from the drive up from Tacoma, I’d press the first button of five presets, programmed to 90.3 FM. I’d heard for a long time Seattle had a “cool” non-commercial radio station, so I made the presets back in Tacoma when all I could hear was garbled static.

Passing through Fremont to get uptown and to the freeway in what was embarrassingly nicknamed (by others, I assure you) “the Green Monster,” the tempo of the Dead Boys' classic single charged me up along with the potent blasts of power chords. After a long spate of mental health issues too numerous to not have their own 5000-word personal essay, I was learning how to live with the riches of self-love and independence (which would take about another decade to fully take root).

I was also trying to find my footing creatively; writing songs on a cheap acoustic guitar given to me for my 20th birthday, writing about music on Blogspot, writing stream-of-consciousness, diaristic posts on Myspace. A sense of identity whipped me in the face while listening to “Sonic Reducer” and plowing across the bridge in my boat of a car while a battalion of Subarus got the hell out of the way.

You see, dear reader, I too had the delusions of grandeur mentioned in the song; the desire to be a great artist and a person of note. And it was what drove me while working an endless stream of demoralizing retail jobs, writing every single day for over five years and not getting paid for the hundreds of thousands of words I spilled on digital pages on servers across the world. The recognition was what pushed me through feeling like a nobody and knowing I had talent I hadn’t even begun to tap into.

Though in sort of a messy way very appropriate for punk music — you can’t rule from a golden tomb, because wouldn’t that suggest you’re dead? — “Sonic Reducer” captures the essence of wanting to be great.

Of course, this listening experiment is also significant because it began my love affair with (and subsequent employment by) KEXP. Which is another personal essay for another time.

You wanna stay alive so you’ve gotta make money

You’ve gotta make money so you have to keep a job

You have to keep a job because you’ve gotta make money

So you give and you give and you give

We’re a FAMILY here, and you wouldn’t wanna disappoint your FAMILY, would you?

Would you??

The opening stanza of “work won’t love you back,” a would-be labor anthem written in a fully just world with great taste, refutes the half-cocked argument of the so-called “Great Resignation” in one fell swoop. Because this is what the meat grinder of capitalism does with its handle; it goes around and around and around and around. Furthermore, it requires us to spend so much time away from our (actual) families that it suggests the relationship we have with our employers is a generational, ancestral bond.

Even daddy’s boy frontperson Jes Skolnik seems to suggest the sort of draining obligation to toxic environments that link the professional to the familial by the way they sneer the word family in the first verse of the truly excellent punk album GREAT NEWS!

daddy’s boy describe themselves as “questionably a hardcore band,” hilariously selling themselves short while still containing a germ of accuracy. At times, Skolnik’s priceless rants are swallowed whole by the din of guitars and drums (all recorded by Midwest punk legend Steve Albini), but those words are more than worth leaning into and risking tinnitus to try and hear.

This is the part where I should disclose that I’ve known Skolnik a long time and consider them a good pal; I first met them after a show with one of their old bands at a small bar in Logan Square in 2011. I watched them take a few different career paths before becoming one of the most insightful music journalists and social justice commentators around (and one of the few truly reasonable voices on Twitter); I watched them ascend to the truly unbeatable editorial staff of Bandcamp Daily (where, another full disclosure alert, I’m known to write from time to time). They’ve engaged with their creativity the entire way through, playing in about half a dozen bands (at least that I know of) in the time I’ve known them.

There is a cliché about how most music critics are failed musicians, but fewer conversations about people who happen to work in music journalism because they have a very clear idea of how they’d like to sound, of what would potentially work for them artistically and what wouldn’t. Besides, who can live solely off of being in a band in 2022 without a trust fund or an exorbitant record deal?

Before I get too far into the lyrics of GREAT NEWS!, it’s imperative to point out the three instrumentalists in daddy’s boy and their stellar contributions. The combination of Bryan Gleason on guitar, Jon Strasheim on bass, and Neal Markowski on drums proves to be limber and muscular; a sprint of propulsive, clattering, pulsating drums; punishing, subatomic, blistering bass; and nervous, dissonant, bleating, scribbling, squealing guitar.

“boston key party” contains a sense of chaos that feels loose but is remarkably precise underneath the surface. “superspreaders” is wound so tightly you almost expect its springs to snap midsong. At nearly double the length of half the songs on GREAT NEWS! (with an epic runtime of 2:19), “do u guys like music” offers a full sense of tension in its pacing. Going back to the notion of clichés, one exists among anti-hardcore types that suggest once you’ve heard two or three hardcore bands, you’ve heard them all. daddy’s boy proves that adage to be sour grapes by finding fascinating new musical and rhythmic pockets for the form.

Somewhere between the cheeky hip-girl schtick of Wet Leg and the self-seriousness bordering on self-parody of Chat Pile are a generation of punk and punk-leaning bands led with the exceptional lyricism of a vocalist who actually has Something to Say. Skolnik’s pen is laced with a beguiling blend of assertive uprightness and acidic sarcasm, delivering manifesto screeds and miniature vignettes both funny and vivid. Not to mention a noble reticence to shrug off the things about society that really bother them.

“Oh well, whatever, never mind” this is not.

In the hands of such a talented writer, of course the songs of daddy’s boy would be driven by Skolnik’s trenchant and hysterical missives. “boston key party,” a thunderous rebuke of the legislation of child-bearing and trans people’s bodies, sits side by side with a note-perfect satire of shitposters and social media influencers (“the poster”), followed in violent succession by a visceral meditation on police titled “superspreaders.”

“family cat” brings the lens down from the positions of the cops and landlords and the mayors and presidents and “the quacks and the podcast hosts” with blood on their teeth and focuses on musicians trading in fake indie cred for sponsorships and magazine covers and delusional self-importance. Try to listen to Skolnik’s spoken-word outro where they deadpan, “I know we’re totally anti-corporate, but I’m creating a safe space for all the oddballs and freaks” without bursting into laughter. Unless you don’t find it funny because you know you’re the target.

After the assault of performative, reactionary politics bearing the title of “do u guys like music,” GREAT NEWS! ends with the atomically funny (and awesomely titled) “new york city jort authority,” where the toll of the impending collapse of society all crashes down on our too-reliable narrator while they try to talk to girls.

The album ends with a statement-of-purpose for the ages: “I’m fun at parties! A real hoot!”

You couldn’t get into fist fights onstage with fans or deliberately swing mic stands into the faces of potential attackers during a set. As was evidenced by a certain weirdly infamous indie-rock article, you couldn’t talk shit about boring indie bands and the boring scenes they come from without alienating your friends in the “indie music industry.” You couldn’t do the sorts of things that would get you kicked out of Gonerfest of all places — where I once saw Timmy Vulgar light up a smoke bomb and attach it to the neck of his guitar mid-song like it was nothing — and still have a notable, popular, somewhat lucrative career.

No, friends, acquaintances, and people who hate-read my work and plagiarize me on the sneak; you couldn’t name yourself Jay Reatard in 2022, regardless of the fact that it was a way to strike back at the language used to taunt and bully a young and troubled Jay Lindsey. You couldn’t write and record a violent and nihilistic punk rock masterpiece like 2006's Blood Visions without a little blowback, even if you played all the instruments yourself.

This is probably all for the best. In an age where even the most popular recording artists in the world are being pressured to redo songs with lightly ableist language, your early claim to fame most certainly couldn’t be a band called the Reatards. We as a society — well, some of us — are learning to be more sympathetic, more compassionate people.

But as we learn how to better care for people who are marginalized differently from the way we are marginalized, for the love of g-d, you couldn’t be a surly, bitter, negative, confrontational asshole in a music world where your value is wholly determined by how well you play with others.

I was already aware to a degree. I was already politicized to a degree. In my Honors World History class my senior year of high school, I wrote and recited a report on Election Day 2000 about how as Governor of Texas, George W. Bush had pardoned dozens of white men on death row in what would be his final days in office and did the same for exactly zero Black and Latino men. I knew the draining effects of misogyny and patriarchy … to a degree.

But back in those days in an ultimately failed struggle to fit in as a “normal” person, I compromised myself. Having a childhood rife with abuse made me sensitive to abuse as a concept, but I most certainly perpetuated some stereotypes of masculinity that, truth be told, didn’t really come naturally to me.

I rode the slow train to reform over the next few years until a Molotov cocktail (pardon the cliché, but it fits) was lit and thrown into my consciousness in the form of a band called Bikini Kill. This fundamental tool of honorable rebellion was introduced to me by a friend ultimately rejected by the whiteness of second-generation riot grrrls in Olympia — a person longtime readers of my writing for this website know as Que Linda. A Dominican punk the white girls in the scene alienated partly out of unspoken fear and reluctance to understand.

As a kid who grew up — like many of the micro-generation I belong to: elder/geriatric millennials — obsessed with Nirvana saw past the notoriety of Kurt Cobain’s addiction and infamous marriage, instead gaining a lot from his taste in music and personal politics, I always knew of Bikini Kill by name and reputation rather than by their songs. Among many other bands I can count among my favorites, Que Linda provided me with the education.

I’m not going to use this forum to tell you all or even any of the things I learned from Que Linda and my other cis and trans women and non-binary friends about feminism, because I think that’s kind of tacky. I’m not going to share our discussions about Girls to the Front, a book she referred to as “the Dead Sea Scrolls of white punk feminism,” which was long on history and information and comparatively short on self-interrogation, because we all know that self-interrogation has devolved into mere performance.

But I will say the things I’ve learned from listening to staunchly feminist bands — from Bikini Kill and Bratmobile and Heavens to Betsy to Tacocat and Childbirth and sadly defunct Vancouver punks Jock Tears — have been instrumental in my growth as a person; in my understanding of the vast many-sidedness of identities and experiences and perspectives; in my ever-present interest in people who are different from me; in my interest in how I am different form others.

My upbringing as a Black kid in America consisted of learning some of the things my ancestors did to advance the radical cause of actually getting white people to humanize us in their minds, but my childhood didn’t offer many answers to the question “why?” Engaging with feminism through punk music set me on the path of learning institutional behaviors and how to fight back instead of simply feeling like these things shouldn’t happen. Why us cisgendered men feel entitled to do and say the things we’ve historically done and said, particularly to people who aren’t cis men. I used to think the word “why” was the most annoying word in the English language until I realized the word is the key to true understanding.

It’s interesting because punk rock feminism helped me understand my place in the world as a Black man, the microaggressions and marginalization that come with it, and the ways white people try to suppress our voices when we’re loud about how (white) society tries to keep you under their thumb. It led me to bands like the Slits and X-Ray Spex and New Bloods, to crucially important zines like Shotgun Seamstress.

In a lot of ways, my education in the realm of feminist punk music was a formative experience in crafting my own style as a writer. The music I was listening to was raw, intellectually challenging, very funny, sometimes outright harrowing and even disturbing. Sometimes I want my writing to feel like a punch to the stomach; other times I want it to feel like a soul-purging conversation over cigarettes on somebody’s porch (even though I’ve never smoked cigarettes). It’s due to the influence of this music that has double-dared me to do what I want and be who I will.

It’s called The Motor City, for shit’s sake. Of course Detroit’s best punk bands came from the garage.

The Stooges, the Gories, the White Stripes, Protomartryr’s first album. Countless untold others. Detroit has a rich history of bands existing in the space between punk and the place where you’re supposed to park your car in inclement weather. One of the great cult figure groups of this city’s extensive musical history comes from this lineage, too; a band named after a synthetic material best known for being wrapped around houses.

Somehow the punk band that uses this name never got sued. I feel as though iconic Swedish post-punks Kleenex are owed a very late apology by someone.

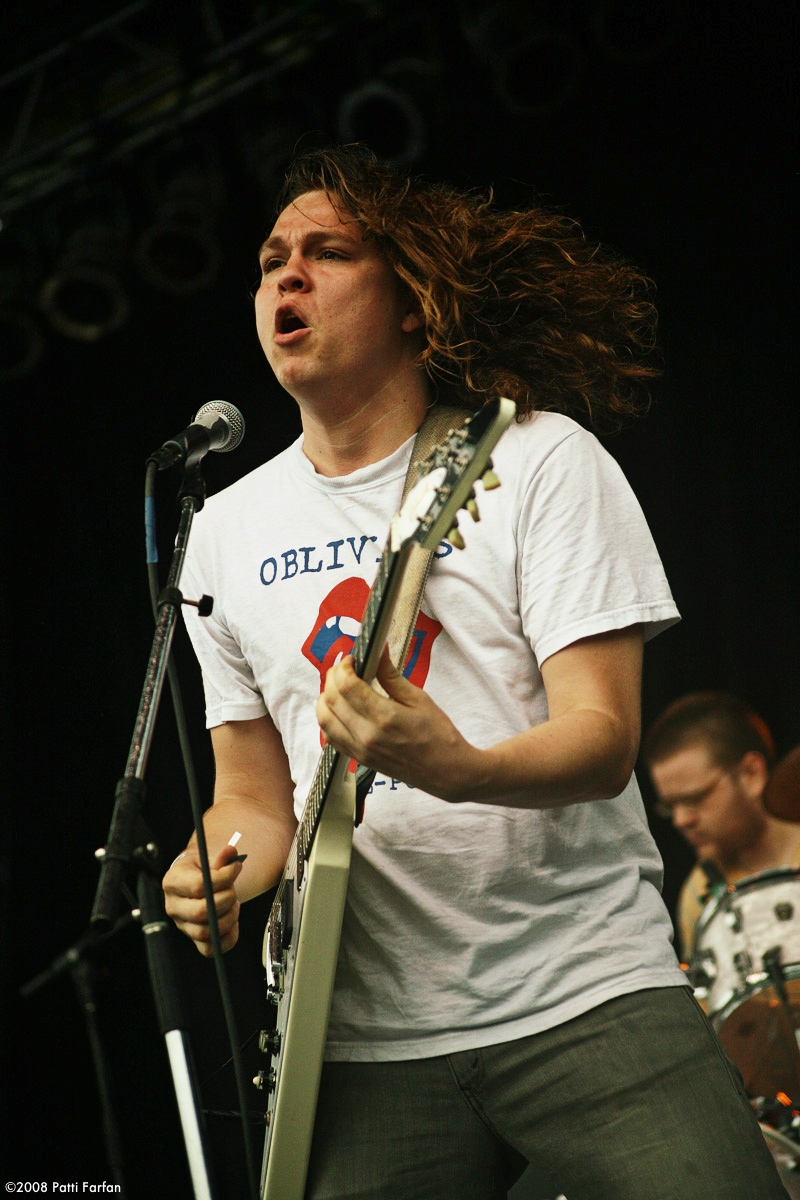

A great deal of my favorite garage-punk music straddles the smart-dumb divide; Tyvek glides across that tightrope effortlessly. As a sufferer of gifted child syndrome turned highly functioning underachiever, I hear that “too smart for your own good” gift for observation crouched in singer/guitarist Kevin Boyer’s sometimes-tuneful bark. Musically, Tyvek are certainly arty; you can hear it in the noise freakout that serve as exclamation points on “Stand and Fight” or the harsh realm ambient coda floating like dirty water through the final two minutes of “Outer Limits.”

But that highfalutin sensibility often takes a backseat to rhythm guitar sloppy enough to leave a sizable stain on your shirt, and Boyer sings like he’s getting in some kicks after sixth period on his day off from the pizza joint down the street. Boyer’s songwriting is uniformly – if deceptively – brainy, singing about Little Richard and Michigan and yuppies and even a girl on a bicycle. And though it’s plenty artsy at points, the musicianship often wobbles like a bike tire about to fall off.

Boyer’s talents as a lyricist always slap me in the face whenever I hear “Underwater I,” the first part of a trilogy which closes with a dubplate playing Origin of What to its end. “Underwater I,” a clear highlight of 2010’s Nothing Fits, swings its elbows as a slowed-down version of D.C. hardcore, speeds up the pace and timbre of what you’d normally expect from Tyvek, rinse, repeat. After shouting a laundry list of appliances and states of unrest that unfolds visually like an aggressive Terrence Malick montage, the image that lasts the longest is a leg shaking off a discarded Safeway bag.

It was around the time of Nothing Fits, an album I described using the word “thrash” as a descriptive term and not one of punk’s many imperceptible sub-genres, when someone called me out on Tumblr. I was told in no uncertain terms that Tyvek was in no way “thrash” and I may not really be punk! Look, do I need to forgo using colorful words as to not be misunderstood? Do I need to know the fucking difference between powerviolence and grindcore to be a punk?

Between this Tumblr user (in a gesture of backlash for feeling excluded from a very particular circle of Tumblr friends I was a part of) and the marginally famous punk musician who stamped me as “boring” in a subtweet (flexing their cred as the frontperson of the sixth- or seventh-best band in their scene), I realized how silly the criteria for inclusion is. How self-identification turns into something totally different when people who don’t know you try to dictate the terms.

Thank goodness for people who protect the sanctity of punk from boring posers like me. O ye real, authentic punks! Hold your keys steadfast, my shepherds!

Last year, I started following a Twitter called Every Nigga Deserves. It’s a not-quite-daily catalog of affirmations, pick-me-ups, and inspirational coaching. It’s a real pat on the back for me and my niggas. Sometimes it’s a pat on the back meaning congratulations and sometimes a pat on the back meaning today was hard and tomorrow will be new.

“May you realize your potential, my nigga.”

“Don’t be afraid to fail, my nigga.”

“Listen to your heart, my nigga.”

“Don’t let anyone dim your light, my nigga.”

I think about all the forces that hold me and my niggas down; forces too numerous to even think about listing in an article already wildly careening past 3000 words. The last quote above hits me the hardest, when taking stock of the world I live in, where I’m surrounded by people trying to dim my light. And that’s not only counting the vast expanse of white people in the suffocatingly white state of Washington, with all their fake modesty and fake diplomacy, afraid my light will expose what their shadows hide. I’m also talking about brothers (and others) who don’t understand punk rock niggas; our jeans are too tight and our music is “too white.” Because every nigga ain’t your nigga, you know?

I’m not gonna pretend I fanboy out over everything Soul Glo puts out (but I’ve been keeping tabs on the white folk who are enthusiastic about them to degree of fetishist tokenization), but The Nigga in Me is Me spoke to me mightily. It finds the band confronting its audience in a way I’d naturally appreciate. (You should have seen some of the emails I received after “Who Stole the Soul from Rock ‘n Roll?” was published.) It’s raw, it’s punishing, it’s belligerently weird at points.

The Nigga in Me is Me hurls righteous fury and violent skepticism of the purportedly good intentions of socially conscious white people at your eardrums like a battering ram. In under 18 minutes, the album casts an eye on your white friends carrying tiki torches, turns their very real (and very publicized) brush with state police into a rebuke of performative allyship, and puts a stop to the age-old Black tradition of selling off their trauma to be able to afford to consume garbage as sustenance.

Soul Glo also adds a dose of euphoria that comes with self-recognition (“Congratulate me, a nigga’s finally free!”) and a healthy serving of corroded bounce, for all of us punk rock niggas who were raised on rap with equal religious fervor.

I recently attended an outdoor screening of the 2003 documentary Afro-Punk, directed by James Spooner (whose coming-of-age punk graphic memoir The High Desert, is equally excellent). One thing I loved about the film that I forgot was the gloriously messy process of finding your identity when you participate in counterculture, especially when said counterculture is erroneously stereotyped as white.

That particular feeling of alienation is not entirely a thing of the past, but being a Black punk is more commonly accepted than it was in my nascent stages of being a punk rock nigga. A band like Soul Glo can be appreciated on their own terms. Indie rock bands like Big Joanie are legitimately making the genre cool again, taking it back from the bland, overly marketed, adult alternative sea of vanilla pudding it has been for the past few years. Taking it back to when indie rock was a sibling offshoot of punk rock music.

I might still be the only black guy at the indie rock show sometimes, but at least there isn't a white guy behind me making a United Colors of Benetton joke. We've still got a long way to go, but that's a minor win for me and my niggas.

Martin Douglas digs for the Black roots of rock 'n roll music in this personal and historical essay.

To culminate KEXP's Punk Month, Martin Douglas explores his life through the cracked prism of punk rock music.